Welcome to Bookmarked, a weekly newsletter following my journey as I read one book from every country. If you’re a new reader, welcome! If you like the sound of my project, I’d love it if you shared Bookmarked with a friend.

In 2016, Moroccan-French author Leïla Slimani’s Lullaby—a thriller about a murderous nanny—sold 600,000 copies in France, making Slimani the most read author in France that year. The book won the Prix Goncourt and was subsequently translated into over 30 languages. But though it was Lullaby which established Slimani’s international reputation, it was the reaction to her debut novel Adèle—a book about a sex addicted journalist living in Paris—which prompted her to write Sex and Lies.

Slimani, who grew up in Rabat and moved to France at the age of 17, conceived of Sex and Lies during a brief promotional book tour for Adèle in Morocco. “The two weeks of my tour were a true revelation,” she writes, describing how readers would approach her after hearing her speak and confide in her their stories about sex. These conversations form the bedrock of Sex and Lies, a nonfictional collection of essays in which Slimani meets and interviews 16 young women (as well as two men) who are navigating Morocco’s oppressive sex culture.

In Morocco, sex before marriage is punishable with a one year prison sentence; adultery with two years; and homosexuality with three. Abortion is illegal, except in cases of rape, severe embryo deformity, or incest. The result, according to Slimani, is a highly politicised sexual culture in which “sex is a constant source of obsession.”

When I was a teenager, everyone I knew could be split into two groups: those who were doing it and those who weren’t. The choice, for us, cannot be compared to that made by a young woman in the West because in Morocco it is tantamount to a political statement, however unwittingly. By losing her virginity, a woman automatically tips over into criminality…

Slimani does a good job at explaining how sexuality is filtered through economic and class-based structures, highlighting how dangerous sex becomes when it is forbidden—especially for those who don’t have the means to pay off police. She also offers a fascinating exploration of the fetish of female virginity, with many of her interviewees describing the process of obtaining premarital virginity certificates from their fathers or doctors.

Among others, Slimani introduces us to a middle-class woman saving up to “have her hymen restored,” a therapist who has walked out on two violent marriages, and a sex worker who supports her parents financially. In one of the book’s most interesting chapters, Slimani interviews theology scholar Asma Lamrabet, who suggests that Morocco’s obsession with virginity is a European import. Despite having combed the Koran in its entirety, Lamrabet says she has been unable to find a clear passage banning premarital sex.

Slimani is careful not to paint Morocco as a country divided by victims and oppressors, but rather as a country in which everyone is suffering from a repressive legal framework. She preempts criticism from both sides: both accusations of glorifying western values and of “purveying ‘orientalist cliches’.” To these ends, Slimani makes an effort to explore the effects of colonialism, noting that in the case of homosexuality, Morocco’s penal code is verbatim the same as the French laws repealed in France in 1982. Slimani herself hopes that Morocco will find its own answers to the issues it is facing rather than adopting western ideas wholesale.

For a long time, I bowed to the notion that to impose my views on others amounted to a kind of condescension. Now I think the only thing that matters is the validity of my argument.

Of course Sex and Lies could have been longer. The book would have undoubtedly painted a more complete picture of attitudes towards sex and sexuality in Morocco if Slimani had interviewed more people, or indeed people from a wider range of backgrounds. But Sex and Lies isn’t an academic textbook and, as long as you’re OK with that, it makes for passionate, candid, and nuanced reading. If Slimani’s goal was to give a voice to those who have been silenced, she achieved it 18 times over. I know I learned a lot from this book.

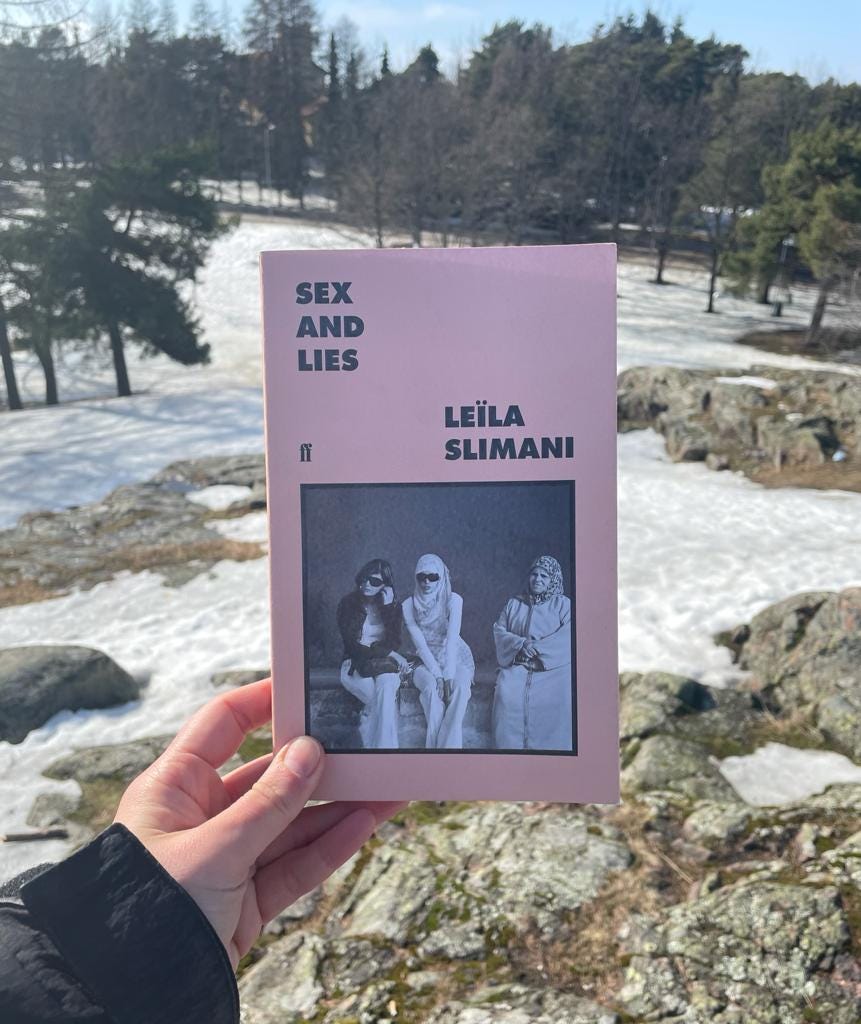

Sex and Lies by Leïla Slimani, translated by Sophie Lewis (Faber & Faber, 2020 / Éditions Les Arènes, 2017)

More books by Moroccan authors:

Here’s a list of the other recommendations I received this week:

The Director and Other Stories from Morocco by Leila Abouzeid

Straight From the Horse’s Mouth by Meryem Alaoui, tr. Emma Ramadan

Ala Dayne by Mhani Alaoui

Dune Song by Anissa M. Bouziane

The Last Patriarch by Najat El Hachmi, tr. Peter Bush

Conditional Citizens: On Belonging in America by Laila Lalami

The Other Americans by Laila Lalami

Dreams of Trespass: Tales of a Harem Girlhood by Fatima Mernissi

Adèle by Leïla Slimani, tr. Sam Taylor

Lullaby by Leïla Slimani, tr. Sam Taylor

What have you read recently?

If you’ve read a brilliant book in translation or want to pass on a recommendation, I’d love to hear about it. For this project, I’m focussing on contemporary fiction and short stories, with a preference for female authors—but as you’ve seen today I’m happy to venture further afield for a good recommendation!

You can get in touch by replying to this email or leaving a comment. I’ll be featuring your recommendations in upcoming newsletters, and I’m keep a growing list of everything I’ve read here.

Bookmarked is written by Tabatha Leggett. If you know someone who would enjoy this newsletter, please forward it to them!